Boardroom battles and taking on Thatcher: How a former BBC NI controller fought a war for independence

A two page spread in The Belfast Telegraph, covering the book, details Sir Richard’s Francis’ time in Northern Ireland

On March 30, 1979, a car bomb exploded outside the Houses of Parliament in Westminster, London.

It claimed the life of MP Airey Neave, striking a blow not only at the heart of the British Government, but also at the heart of Margaret Thatcher who was on the cusp of leading her Conservative Party into Downing Street.

The INLA claimed responsibility for the blast that took the life of the Shadow Minister for Northern Ireland and a close friend of the PM in waiting.

Within weeks of the assassination, Sir Richard (Dick) Francis, put representatives of the terror gang on BBC Television.

“He didn’t do it to provoke or to grandstand as might be the case in today’s climate of outrage television. He did it because, as Director of News and Current Affairs at the BBC, he believed the British public had a right to hear the truth — even when it was grim and even when it hurt,” his son, historian Stephen Francis says.

“The interview aired, triggering political outrage. Thatcher denounced it in the Commons and the grieving Lady Neave complained, yet the BBC stood its ground.

“That decision — and many like it — came at a cost. But it also defined a generation of management at the BBC that had to have understood courage, consequence and moral clarity. Dick Francis was one of them.

“In fact, I’d say he was the last of them.”

That decision, Stephen Francis argues, upheld everything the BBC stood for as laid out in its Royal Charter which states “the Corporation is required to refrain from broadcasting its own views on current affairs and matters of public policy”.

The same sentiment is reflected in a 1960 report for the BBC General Advisory Council that stated “the BBC does not hold or express an editorial opinion of its own”.

These explicit regulations and directions within the organisation, Stephen argues in his book, which looks back on the life of his father in media, have been lost in the decades since.

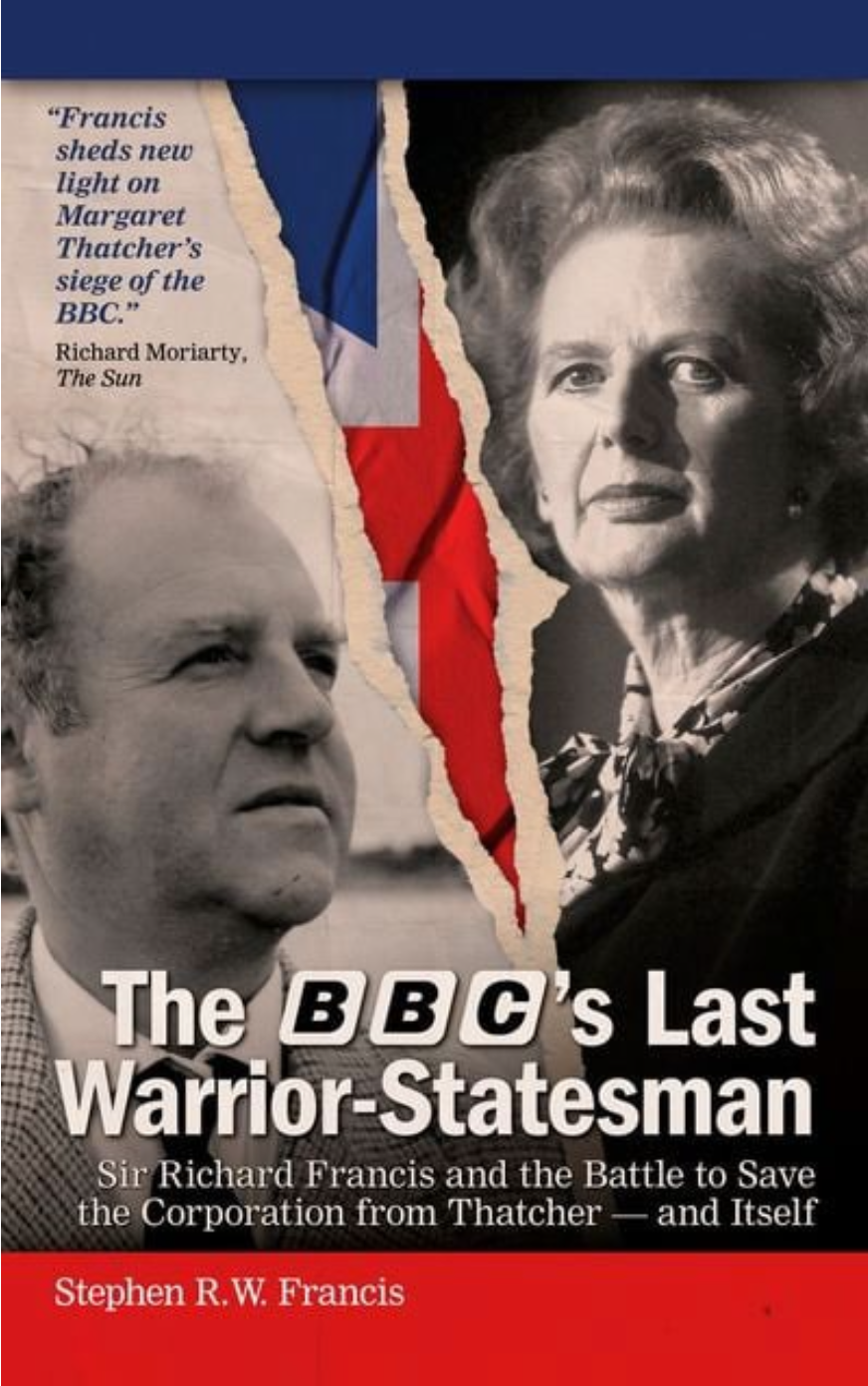

The BBC’s Last Warrior Statesman, by historian Stephen Francis, son of former head of BBC NI Sir Richard Francis

The BBC’s Last Warrior-Statesman documents how, during the 1970s and 80s, Sir Richard Francis oversaw fuel runs across IRA checkpoints, greenlit broadcasts of a politician’s killers, and stood firm against PM Margaret Thatcher, all to defend the BBC’s editorial independence.

It focuses on the battles in the BBC’s boardrooms, from the height of the Cold War to Belfast, from the Falklands to Whitehall, arguing that what happened then is happening again, only this time without men like Dick Francis to hold the line firm against outside influence. Stephen sums up the current state of ‘the nation’s’ broadcaster as: “The BBC, once the most trusted voice in the world, is now cornered, cowed, and too often compliant. It is led by commercial executives, not war-hardened diplomats. It fears controversy more than irrelevance. It talks of principle but, perennially short of funds, it shrinks annually, retaining the popular too often at the expense of the good.”

The protracted removal of Match of the Day host Gary Lineker over a personal social media post, concern over editorial choices, with the recent decision to remove a documentary Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone off iPlayer, offering more fuel to those accusing the corporation of editorial bias.

In the last week, BBC NI itself has been in the headlines again, accused by the Orange Order of misleading the public over opposition to a GAA summer camp in Comber.

The BBC controversies have come almost as quickly as the news itself.

The Royal Charter, which comes up for renewal at the end of 2027, demands it serve the public interest, not chase popularity. That, Stephen’s book argues, is exactly what his father fought for.

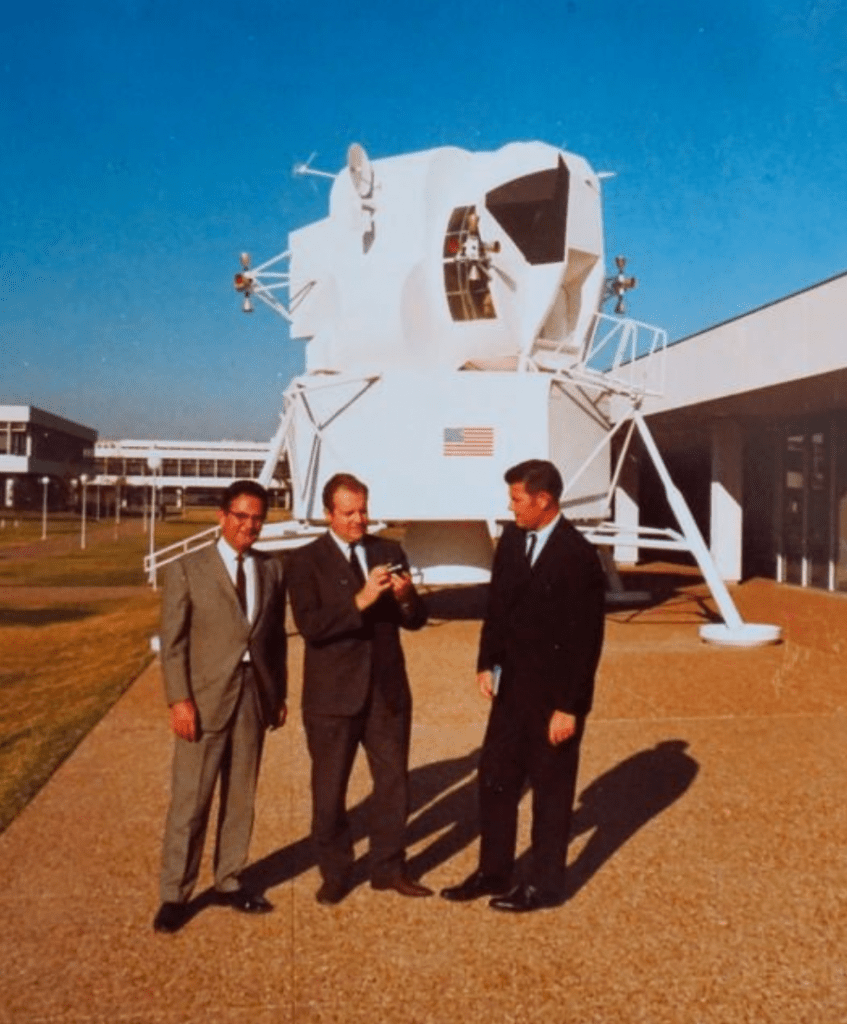

Before his appointment as Controller BBC NI in June 1973, he had been a war reporter — including in Vietnam — and had also led the BBC’s coverage of the Apollo moon landings in July 1969 — hailed as ‘the greatest media event of all time’, and the near disaster of Apollo 13 a year later.

“The cocktail of Northern Ireland was to test the BBC more than any other event in history,” writes Stephen, explaining that his father was drawn to Belfast, “like a moth to a flame”.

He quickly lit fires of his own, both within the BBC and with a succession of Prime Ministers, notably Margaret Thatcher.

He arrived in Northern Ireland as the BBC faced criticism for coverage of Catholics being burned from their houses in west Belfast. No mention was made of ‘catholic’. The BBC needed to up its game — and in 1971 current affairs programme 24 Hours featured an episode on the Provisional IRA, carrying an interview with two masked members. The reporter in question — Bernard Falk — refused to reveal the sources and was sentenced to four days in jail following an RUC investigation.

The BBC in Northern Ireland faced critical editorial decisions virtually every day.

“On January 5, 1972, the BBC broadcast a highly controversial three-hour special, The Question of Ulster,” Stephen writes, “debating the future of the province in the light of the sectarian troubles that seemed to be intractable and increasingly violent.”

Sir Richard was the creator and producer and Stephen, through previously unseen diaries, personal letters and internal BBC memos, highlights how the BBC wrestled with the potential consequences and the efforts to bring all parties to the debate.

“His handling of that marked him down as an outstanding candidate for high office in the BBC,” he writes. “He was now particularly well qualified for a senior role in BBC NI itself.’

The top job in NI was soon his, “the most bloody awful and dangerous,” Stephen writes.

“There was a realisation at the time that it was going to be even more important to pursue normal programming as an antidote to the inevitable bad news”

It did come at a cost to his family life.

A recollection from Sir Richard’s sister Sue tells: “We’re driving back into Belfast. Looking over his shoulder, he said, “I don’t want to worry you but there’s a car that’s been following us for quite a long time. What I’m going to do is turn into a lay-by very quickly. If the car behind slows down, I want you to run for it.”

The car actually belonged to a neighbour, but the threat was felt. BBC staff, said Stephen, had to have a hire car and change it once a month so people couldn’t track them. Those were dangers all too clear following a bomb at Broadcasting House in Belfast on June 14, 1974. The offices had been cleared, and after a few minutes, staff were back at their desks.

Sir Richard oversaw fuel runs across IRA checkpoints, greenlit broadcasts for interviews with those representatives of the group claiming responsibility for a politician’s murder and despite the mounting criticism from Westminster, he refused to bow to pressure from outside influence.

Among his critics was MP Airey Neave, writes Stephen, who called for restrictions on newspapers and television.

Sir Richard’s response did not go down well.

“If the violent activities of terrorists go unreported, there must be a danger that they may escalate their actions to make their point. If we don’t seek, with suitable safeguards, to report and to expose the words of terrorist organisations, we may well be encouraging them to speak more and more with violence.”

Amidst the troubles on the streets and in the BBC boardroom, New Year’s Day 1975 saw Radio Ulster take to the airwaves for the first time.

“There was a realisation at the time that it was going to be even more important to pursue normal programming as an antidote to the inevitable bad news,” Sir Richard reflected.

In early 1977, his stance led the broadcaster to interview two members of the recently formed INLA who were claiming several murders in south Londonderry. By the end of the week, the INLA was a proscribed organisation.

Two years later, having left BBC NI to become the BBC’s Director of News and Current Affairs, it was his insistence on interviewing INLA members again in the wake of the murder of Airey Neave and the running battle between the BBC, and the soon to be Prime Minister, was underway, despite Sir Richard’s insistence that “the people who saw the programme were much better disposed to the security forces and much worse disposed to the terrorists because of it.”

What didn’t help was that there was little prior warning that the interview was to be broadcast.

“Suddenly, without warning, she (Airey Neave’s widow) found herself face to face with a man from the organisation which murdered her husband,” he admitted. But audiences, he believed, were “much more mature than politicians believe and have a right to know.”

That ‘fiercely independent’ streak continued as the BBC covered The Falklands War in 1982, but Northern Ireland affairs were never far from the battleground. And 1985, series Real Lives was to bring the BBC/government relations to a head again.

It set a young Martin McGuinness against a young Gregory Campbell. One a former IRA leader, now MP, with ‘blood on his hands’, the other a hardline loyalist, advocate of a ‘shoot to kill’ policy against the IRA. Thatcher had been speaking vehemently against giving ‘oxygen’ to terrorists. This time she won. For the first time in its history, the BBC banned its own programme, despite the threat to its independence.

On August 7, 1985, the day Real Lives had been scheduled for transmission, the World Service carried no news for the first time in its history, BBC News services were silenced by strike action, and the turmoil that followed almost ripped the corporation apart.

Sir Richard Francis left the BBC in 1986. He died in 1992, aged 58.

“BBC journalists have huge freedom, but with that comes the obligation to be accurate, balanced and uphold the Charter,” said Stephen. “Don’t editorialise or chase popularity. Understand why the BBC exists and stand up to power when needed. The leadership today too often stays silent. My father believed the BBC should be confident, principled and visible — never cowed.

“The book shows why the BBC earned its global trust through fearless journalism, independence and talent. It also shows how easily that position can slip.”